Introduction

The relentless pace of change of the twenty-first century has framed learning as a cultural phenomenon as globalisation, technological advancements and the rise of the digital age have created a need for citizens to become lifelong learners who are constantly up-skilling in order to survive and thrive (Douglas & Seely Brown, 2011, loc 50; Jarvis, 2009, p.15). The digital age has removed many of the physical restrictions placed on learning, as technologies allow us to travel around the world and access a ubiquity of information at the click of a button (Selwyn, 2013, p.2).

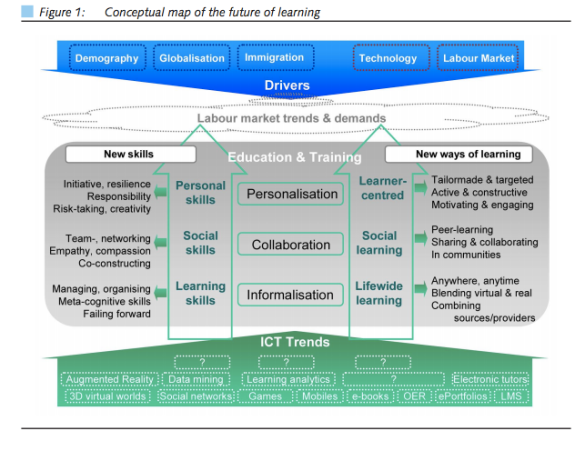

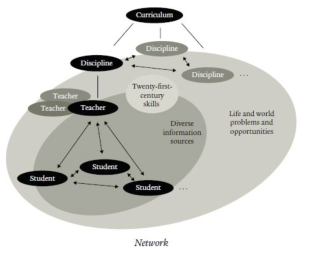

The image above provides a conceptual map of the future of learning and the influence of drivers and Information Communication Technology (ICT) trends on education means that, more than ever, teachers are expected to be adept at a variety of technology-based pedagogical practices in order to promote twenty-first century learning experiences for their students (Johnson, Adams Becker, Estrada & Freedman, 2014, p.6). In response to the ever-changing notions of learning in the twenty-first century, Perkins suggests that educators must begin to provide learning experiences that are both ‘lifeworthy’- “likely to matter in the lives learners are likely to live” (2014, p. 8), and ‘lifeready’ – “ready to pop up on appropriate occasions and help make sense of the world” (2014, p. 24).Consequently, as educators in this society, to offer lifeworthy and lifeready learning to our students, our classrooms must become what Boccini, Kampylis and Punie describe as ‘live ecosystems’, environments that constantly evolve and change to suit the context and culture of which they are a part (2012). It becomes essential then that we meet the learning needs of students by creating, “a sustainable learning ecology that is shaped by the ubiquity of information, globally responsive pedagogical practices, and driven by collaboration and informal learning in multiple access points and through multiple mediums” (O’Connell, 2015). The greatest challenge for educators in the digital age becomes how to alter their pedagogy and curricula to provide lifeready and lifeworthy learning for students that will be likely to matter to them in their future (Perkins, 2014). Therefore networked concepts such as expert amateurism and connected learning are essential starting points for educators in ensuring the learning that happens in their classrooms is future-proof.

Lifeready and Lifeworthy Learning

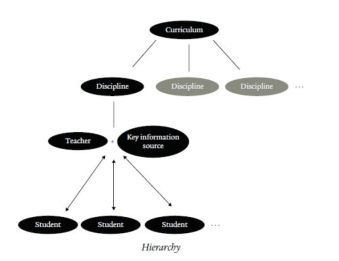

In the video above, Alan November poses some important questions about the role of teaching and learning in the digital age. He emphasises that we must accept the idea of ‘digital natives’ as a myth and acknowledge the fact that, just because today’s learners were born into the digital age, they are not necessarily prepared for learning in the digital age. Thus, we must accept that our society of ubiquitous information access does not make redundant the role of the teacher, as information access does not equal knowledge attainment (Seely Brown & Duguid, 2000). Rather, it becomes the role of the teacher to ensure that all learning experienced in the classroom is genuine, viable and future-orientated. This is where Perkin’s notions of lifeready and lifeworthy learning become, essential for educators of the digital age in ensuring the currency and relevancy of what they are teaching. Traditionally, education in schools has been concerned with educating for a known future, where tried and true hierarchical structures were dictated by curriculum organised into disciplines. Perkins asserts that while a hierarchical structure offers advantages of simplicity and organisation, it does not aptly reflect the learners of the digital age, who are living in an increasingly networked and globalised world, calling educators to rethink the how, what and why of teaching to incorporate the expanding measure of what is worth learning (2014, p.41). Similarly, Douglas and Seely Brown suggest that we must consider the change in learning that happened with the move from the stable infrastructure of the twentieth century to the fluid infrastructure of the twenty-first century (2011, loc. 50).

Thus, a more networked approach to learning that incorporates lifeready and lifeworthy learning is essential as, “a network structure mirrors today’s multiplicity of engagements and serves today’s learners better: disciplines related to one another, teachers collaborating with one another, students interact richly with one another, drawing on diverse information sources, addressing twenty-first century skills, and engaging life and world problems and opportunities” (2014, p.47). It becomes evident then, that educators must begin to consider how the influence of networked environments reshapes the learning that is valued by students in their classrooms and the relevance the learning that takes places will have in the lives their students are likely to live.

Expert Amateurism

The video above articulates perfectly the decreasing value of knowledge attainment alone in a world where we can access all of the information we need online. What is more important is knowing how to ask the right questions and building the skills we need to assist us in knowing what to do when we do not know what to do. Therefore, considering a networked curriculum that caters for expert amateurism, becomes a way for educators to provide lifeready and lifeworthy learning that will enable them to succeed beyond their time at school. Perkins states that an, “expert amateur understands the basics and applies them confidently, correctly and flexibly” (2014, p.38). Furthermore, this notion of expert amateurism serves much of the learning we do outside the school environment in our everyday lives. While not devaluing the role of specialisation and traditional disciplines, expert amateurism has the potential to play an appropriate role at the foundation of our curricula in the digital age. It allows us to practice the skills of lifelong learning as we apply what we know to look outwards towards the networked world around us, instead of inwards towards our insular scholarly disciplines. Of course, our traditional focus on building expertise in each discipline by way of advanced technical content has value later in life as individuals choose to specialise in areas that interest them, however, in our school environments, this is unlikely to have much value to the majority of students in the lives they are likely to live (Perkins, 2014). Embracing expert amateurism allows us to ensure that the students in our classrooms are able to make connections outside of specific learning areas and connect their learning to build greater understanding, just as they do in their everyday life outside of the classroom.

Redecker et al., state that two of the biggest challenges in providing lifeready and lifeworthy learning are: providing transition between the worlds of school and future employment, and focussing on permanent re-skilling to enable all citizens to adjust quickly to new environments (2011, p.10). As educators in the digital age then, we must work to build and model expert amateurism for our students to ensure that learning in the classroom is lifeready and lifeworthy. When we consider the role of expert amateurism in a networked approach to learning, we are providing learning that allows students to use what they know to make connections and reflect best-practice in the digital age, as students are able to go beyond the insular walls of their classroom. Expert amateurism provides students with the basics they need to thrive and survive in the twenty-first century as they navigate their way through an ever-changing and digital world.

Connected Learning

Connected learning provides an approach to teaching and learning that assists educators in building expert amateurism and move away from a hierarchical structure towards a networked structure of learning in their classroom.

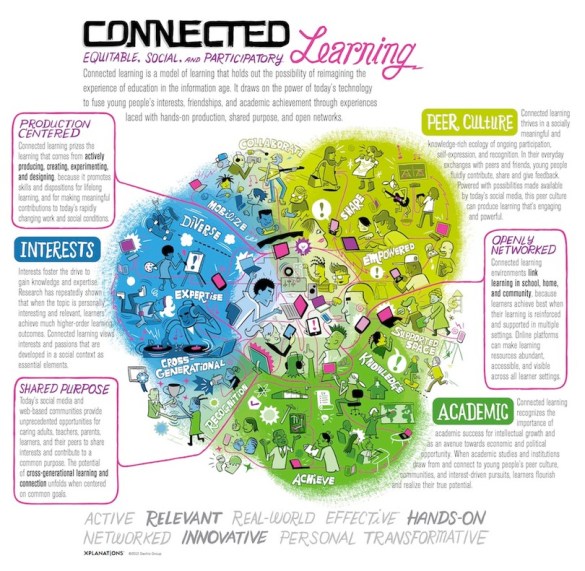

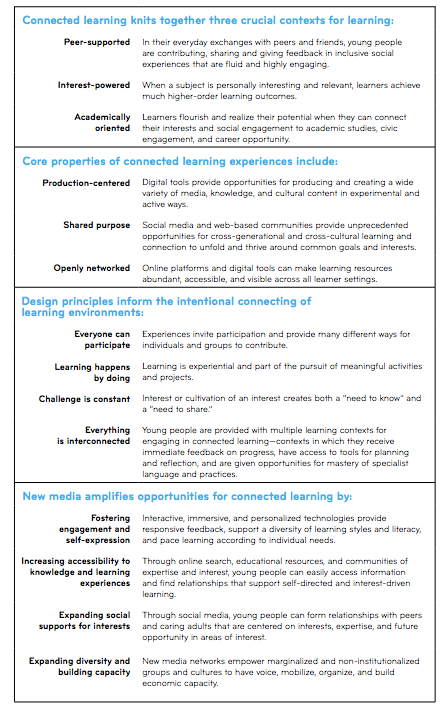

The ever-present change of the twenty-first century means that educators have to seamlessly adapt their practices to suit new technologies, skills, learning environments and the needs of their students (Cantrill, et. al., 2014, p. 4). Outside of school, our students are learning, engaging and producing in productive and collaborative ways, using digital media and networked environments (Cantrill, et. al, 2014, p.6). Thus, while not born in the digital age, the principles of connected learning are befitting of it, as it promotes student-driven connection that requires active participation and collaboration in front of a real-world audience (O’Connell, 2015b). With the world at their fingertips, students of the digital age have diverse pathways in which they can access connected learning, enabling connections between their learning at school and their networks and interests outside of school, providing learning that is both lifeready and lifeworthy. Embracing a connected learning framework in our pedagogical approaches enables us to draw focus away from particular technologies that often take precedent in the digital age, and instead, focus on the value of learning through, “purposeful integration of tools for social connection, creations and linking the classroom, community and home” (Ito, et. al., 2013, p.33). As evidenced in the infographic below, connected learning encompasses production-centred, openly networked learning, that is driven by interests and shared purpose and allows for collaboration and academic growth.

The Connected Learning Framework below demonstrates the ability of connected learning to allow students to look outwards from curricula and create and build connections naturally, based on their interests. With educators both guiding and modelling connected learning, there is much potential to provide learning that is lifeready and lifeworthy and conducive to the digital age.

The video below provides an authentic example of connected learning in practice. The combination of a student demonstrating the notion of expert amateurism combined with connected learning principles in this example attests to the power of learning that is both lifeready and lifeworthy.

Conclusion

The highly networked society of the digital age means that students are coming to school indoctrinated by our culture of lifelong learning, and if we are not careful, will be met with out-dated models of teaching and learning that do not promote engagement of lifeready and lifeworthy learning. By foregrounding the way we learn in the digital age, rather than focusing on knowledge attainment and expertise alone, and embracing concepts such as expert amateurism and connected learning in our teaching practice, we will provide our students with the skills and ability to continue learning in their life beyond school. We must begin to turn away from traditional hierarchical structures of education that could be seen to value what was already prescribed and valued knowledge and focus on building skills in learning that prepares students for learning in the world they are likely to live (Starkey, 2011, p. 19). Siemansarticulates learning in the digital age as, “a process that occurs within nebulous environments of shifting core elements – not entirely under the control of the individual. Learning… can reside outside of ourselves (within an organization or a database), is focused on connecting specialized information sets, and the connections that enable us to learn more are more important than our current state of knowing” (2004, para. 23). As educators, if we begin to explore the notions of expert amateurism and connected learning in our classrooms, we will be well on the way to meeting the needs of digital age learning. If we continue to value the hierarchical practices of traditional education that value knowledge attainment alone, without evolving to more networked structures promoting transferable knowledge and skills, we will not ensure that we are preparing students for lifeready and lifeworthy learning necessary of the digital age. We must begin to embrace a culture of learning indicative of twenty-first century practices in the digital age so that we are preparing students for their future, and not the future we thought they would have.

Reference List

Bocconi, S., Kampylis, P. G., & Punie, Y. (2012). Innovating learning: Key elements for developing creative classrooms in Europe. Joint Research Centre–Institute for Prospective Technological Studies. European Commission. Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg. doi: 10, 90566.

Cantrill, C., Filipiak, D., Garcia, A., Hunt, B., Lee, C., Mirra., O’Donnell-Allen, C., & Peppler, K. (2014). Teaching in the connected learning classroom (ed. A. Garcia). Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Connected Learning. (2013). Connected learning infographic [Image]. Retrieved fromhttp://connectedlearning.tv/infographic

Connected Learning Alliance. (2014). Connected learning: The power of making learning relevant [Video file]. Retrieved from

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=quYDkuD4dMU

Ericsson. (2012, October 19). The future of learning, networked society – Ericsson [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=quYDkuD4dMU

Institute of Play. (2013). Charles Raben, 9th grade student at quest to learn [Video file]. Retrieved from https://vimeo.com/59098372

Ito, M., Guitierrez, K., Livingstone, S., Penuel, B., Rhodes, J., Salen, K., Schor, J., Sefton-Green, J., & Craig Watkins, C. (2013). Connected learning: an agenda for research and design. Irvine, CA: Digital Media and Learning Research Hub.

Jarvis, P. (2009). The Routledge international handbook of lifelong learning. Hoboken: Taylor and Francis.

Johnson, L., Adams Becker, S., Estrada, V., & Freeman, A. (2014). NMC horizon report: 2014 K-12 edition. Retrieved from New Media Consortium website http://cdn.nmc.org/media/2014-nmc-horizon-report-k12-EN.pdf

O’Connell, J. (2015a). INF530 Concepts and practices for a digital age: Module 1.3. Retrieved from https://interact2.csu.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-249311-dt-content-rid-635329_1/courses/S-INF530_201530_W_D/module1/1_3_Trends_tech.html

O’Connell, J. (2015b). INF530 Concepts and practices for a digital age: Module 1.6. Retrieved from https://interact2.csu.edu.au/bbcswebdav/pid-249311-dt-content-rid-635329_1/courses/S-INF530_201530_W_D/module1/1_6_Principles_connected_learning.html

Perkins, D. (2014). Future wise: Educating our children for a changing world. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Redecker, C., Leis, M., Leendertse, M., Punie, Y., Gijsbers, G., Kirschner, P., Stoyanov, S. & Hoogveld, B. (2011). The future of learning: preparing for change. Retrieved from http://dspace.ou.nl/bitstream/1820/4196/1/The%20Future%20of%20Learning%20-%20Preparing%20for%20Change.pdf

Seely Brown, J. & Duguid, P. (2000). Social life of information. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.<span “font-family:arial;mso-fareast-font-family:=”” “times=”” roman”;mso-ansi-language:en-au”=””>

Selwyn, N. (2013). Education in a digital world: Global perspectives on technology and education. New York: Routledge.

Siemens, G. (2004). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. Retrieved from elearnspace website http://www.elearnspace.org/Articles/connectivism.htm

Starkey, L. (2011). Evaluating learning in the 21st century: A digital age learning matrix. Technology, Pedagogy and Education 20(1), 19-39. doi: 10.1080/1475939X.2011.554021

Storm, S. (2013, December 10). #truth #tlap #COLchat :pic.twitter.com/vwd9lUjw3k [Tweet]. Retrieved from https://twitter.com/sstorm01/status/410233387987636225/photo/1

The Brainwaves Video Anthology. (2014, May 5). Alan November – who owns the learning? Preparing students for success in the digital age [Video file]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NOAIxIBeT90

Thomas, D. & Seely Brown, J. (2011). A new culture of learning: Cultivating the imagination for a world of constant change [Kindle version]. Retrieved from http://www.amazon.com/New-Culture-Learning-Cultivating-Imagination-ebook/dp/B004RZH0BG/ref=sr_1_1_twi_2_kin?ie=UTF8&qid=1432974655&sr=8-1&keywords=douglas+and+seely+brown+a+new+culture+of+learning

West, D. M. (2012). Digital schools: How technology can transform education [EBL version]. Retrieved fromhttp://reader.eblib.com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au/(S(l1ttps5hfzo3orl3txdevkfo))/Reader.aspx?p=967462&o=476&u=aIXo0ZBzSmXukM8fp%2fN7GA%3d%3d&t=1432971270&h=423E42B21547D82EE9EE051B312973CF2B315A45&s=36581639&ut=1443&pg=1&r=img&c=-1&pat=n&cms=-1&sd=2#

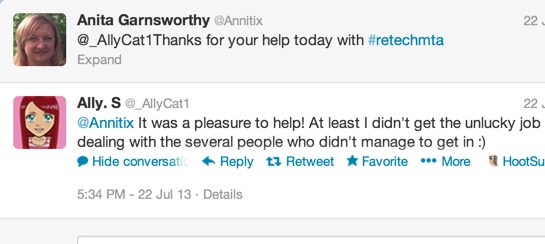

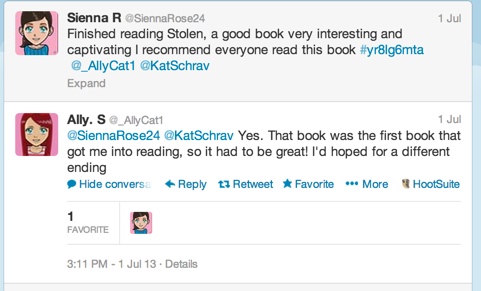

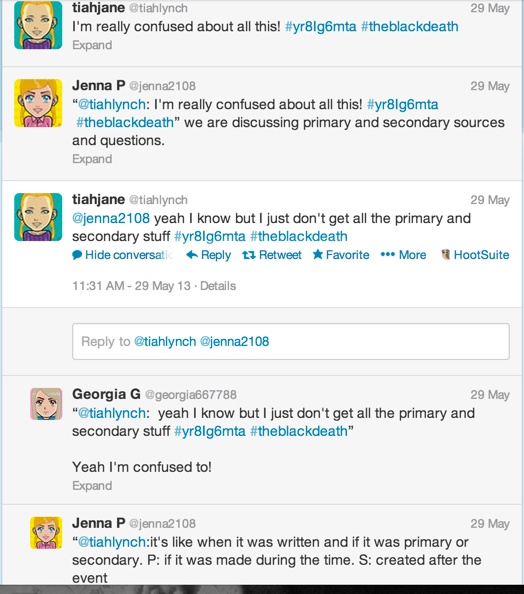

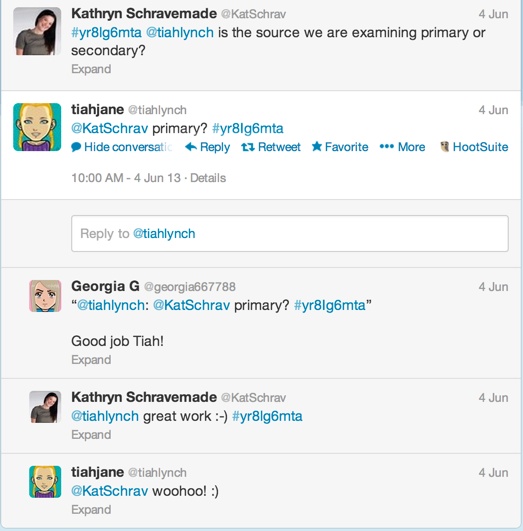

As adults however, we know that what students put online will increasingly affect their job opportunities in the future, as employers can find inappropriate comments, images and interactions with a simple Google search. This emphasises the need for us, as educators, to provide students with real-life examples of positive and negative footprints and model digital footprints through our own actions online, particularly with the emergence of mobile social networking and geo-spatial tagging. For example, I often ‘Google’ myself with students to demonstrate how we can manipulate the information about us online in a positive manner. In my belief, this is just as essential as being aware of cyber safety and responsible behaviours.

As adults however, we know that what students put online will increasingly affect their job opportunities in the future, as employers can find inappropriate comments, images and interactions with a simple Google search. This emphasises the need for us, as educators, to provide students with real-life examples of positive and negative footprints and model digital footprints through our own actions online, particularly with the emergence of mobile social networking and geo-spatial tagging. For example, I often ‘Google’ myself with students to demonstrate how we can manipulate the information about us online in a positive manner. In my belief, this is just as essential as being aware of cyber safety and responsible behaviours.

![Geography class. [Photography]. Retrieved from Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. http://quest.eb.com/#/search/139_1931997/1/139_1931997/cite](https://theprivateteacher.files.wordpress.com/2014/09/139_1931997-w.jpg?w=585&h=394)