“If we teach today’s students as we taught yesterday’s, we rob them of tomorrow” – John Dewey

Introduction

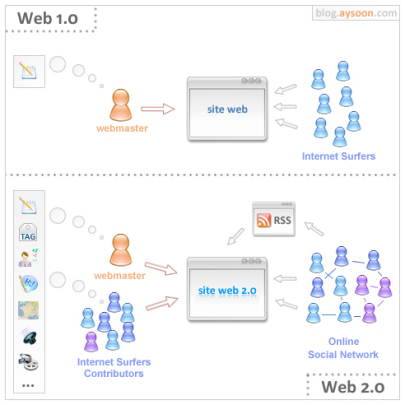

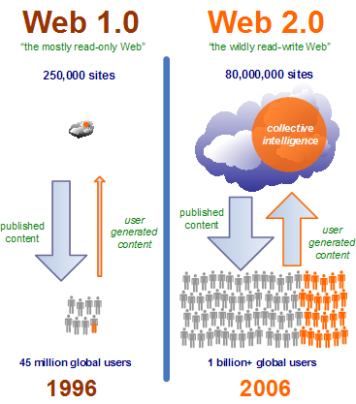

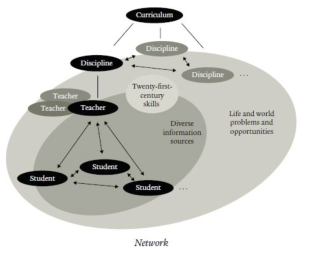

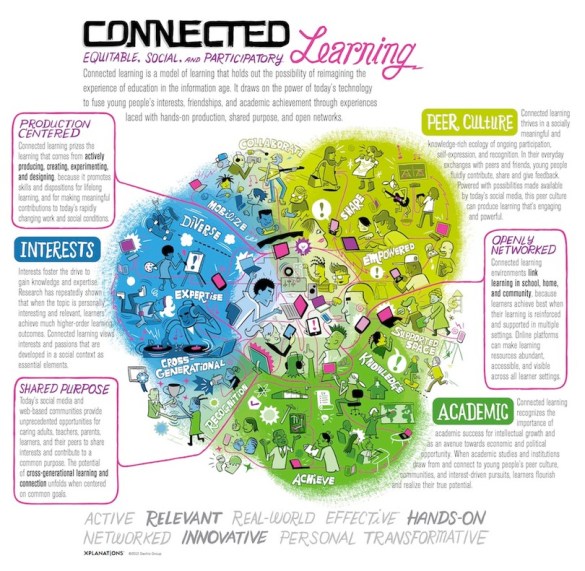

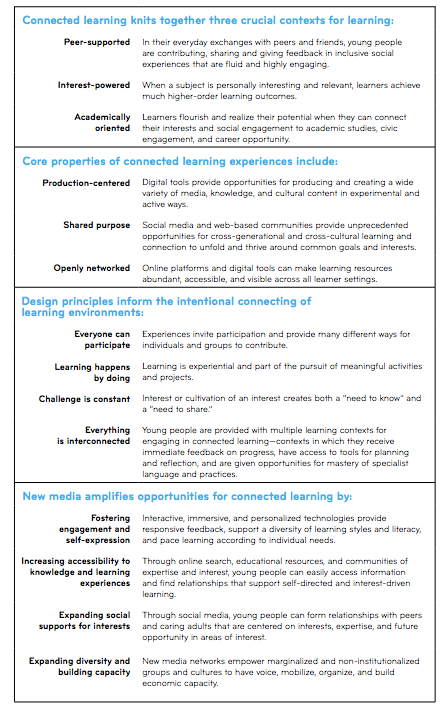

The rise of the digital age, the sudden ubiquity of information and our access to it and the evolution of the static Web 1.0 to the participatory Web 3.0 have enabled an overhaul of what we deem as academic scholarship (Starkey, 2012; Vodanovich, Sundaram & Myers, M, 2010; McCain, Jukes & Crockett, 2010; Levnajic, 2014). Learners are operating in the world of the unknown where the paradigm shift that accompanied changes to learning in the twenty-first century continues to challenge us with new cognitive approaches (Spector, 2010, p.4). As the technologies we are exposed to continue to evolve at such a rapid pace, learning has become online, participatory and social and this, in itself, poses many challenges to the nature of scholarship – a practice that was often undertaken in the isolation of print and static materials (Weller, 2011, p.2). With the impact of technologies on our daily life so great and ‘digital’ now the norm, scholars such as Martin, warn that we cannot become complacent in proffering that traditional academic scholarship has been replaced by digital scholarship (2016, p.3). In fact, we must consider the affordances created by the possibility of new and emerging trends in technology and how these influence the notion of scholarship in the information age (Goodfellow, 2013; Weller, 2011).

Evolution of Digital Scholarship

When Boyer (1990) challenged the traditional notion of scholarship by suggesting that scholars go beyond traditional research to adopt to social, contemporary and environmental changes, we witnessed the catalyst of change in the way academia viewed scholarship. Boyer’s model of scholarship transcended traditional notions to consider a broader approach beyond that of research, to one that recognised, “knowledge is acquired through research, through synthesis, through practice and through teaching” and these four components should be valued equally (1990, p. 24). His four functions of scholarship: discovery, integration, application and teaching set a new framework in the understanding of scholarship and recently, have acted as a benchmark in the consideration of digital scholarship (Weller, 2011; Veletsianos & Kimmons, 2012; Martin, 2016). While it would be easy to label digital scholarship as scholarship using digital means, in reality, digital scholarship goes much further than this. It is the ability of the scholar in the digital age to go beyond discipline-specific formal publications and enter interdisciplinary realms (Goodfellow, 2013). In fact, Esposito (2013) argues digital scholarship to include research practices, “such as – information access, authoring, sharing, networking, publishing – mediated by technology”. The nature of participation in the digital age and technologies such as blogging, back channels and social media have many implications for Boyer’s functions of scholarship as suddenly education has become ‘open’ and ‘available’ online for everyone as opposed to our traditional ‘four walls’ models (Katz, 2010, p.48). With this sudden equality of information available for everyone, regardless of their academic background, the playing field of scholarship has been evened and this calls for the necessity of educators to rethink the learning that happens in their institutions (Katz, 2010, p. 50). What becomes evident however, is whether we are ensuring that scholars have the skills necessary to harness this availability of information through finely honed digital scholarship skills.

Implications of Digital Scholarship for Students

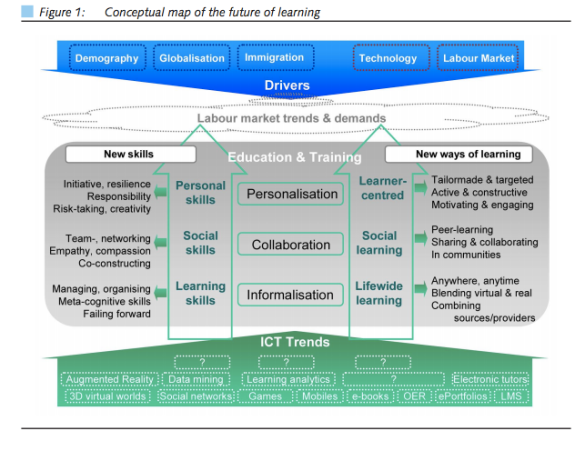

As ‘knowledge’ is no longer attained in isolation and learners are exposed to a range of networks and resources that allow them to interact, collaborate and engage with others in the development of ideas, we must consider how this is reflected in scholarship (Starkey, 2011, p. 22). If the focus of education in our schools and higher education systems is to prepare students to become active participants of society, it becomes evident that the concept of digital scholarship must be considered in the future of learning as our traditional notions are challenged by digital and participatory cultures. The University of Queensland’s Student Strategy 2016-2020 White Paper acknowledges that,

“Digital technologies have fundamentally altered the way we live and work. They have broken down barriers and given rise to a wave of new job titles, a growing virtual workforce and an explosion in personalised online services – all of which are having a profound impact on what and how we choose to learn” (2016, p. 3).

This is reflected in the Australian workforce as employers are increasingly identifying skills reflective of digital practices as a necessity in their employees. In 2016, the Business Council of Australia in Being work ready: A guide to what employers want, identified technical skills, understanding of Information Communication and Technologies (ICTs), data analysis and critical analysis as the four key skills necessary for employees in the current work force. Similarly, The Australian Council of Learning Academics asserted that employees need to, “think in technological terms and know what and how solutions can be achieved through the use of technology” (2016). Reports such as these lead us to question how we are preparing students in schooling and higher educational institutions for their future careers. It is clear that the workforce is demanding skills indicative of the digital age, thus, is academic scholarship alone best preparing students with the knowledge and skills they will need for their future careers of the digital age?

When examined further, it appears that Australia has long recognised the value of preparing students to deal with concepts such as global connections and technological change in our education systems. In fact, the need to increase the effectiveness of student ICT usage was emphasised as an essential consideration in the Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians (2008, p. 5). This sentiment was echoed by the Regional Australia Institute and NBN in The Future of Work: Setting Kids up for Success report that identified information, digital and media fluency as absolutely critical skills for the workforce of the future with the prediction that within two to five years, ninety percent of the workforce will require digital literacy (2016, p.10). Interestingly though, while the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) established the general capabilities (2016), including the ICT capability, in response to the Melbourne Declaration, we are yet to see evidence of the impact of these inclusions in our schooling systems. Most alarmingly, ACARA reported a significant decline in the proportion of students at or above proficient standard in ICT literacy in both Year six and Year 10 across all states and territories in Australia, identifying an increased need to focus on the development of ICT literacies in Australian Schooling (as cited in NSW Audit Office, 2017, p.17). With more educators identifying their practices as inclusive of digital scholarship, yet literacy rates declining, it is necessary to consider what translation this has to learners in our schools (Lippincott, Hemmasi & Lewis, 2014).

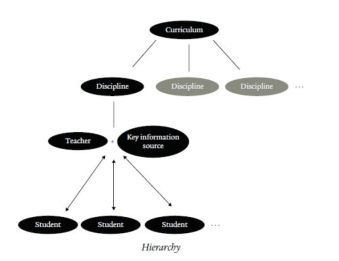

Uptake of Digital Scholarship in Schools

Perhaps the misinterpretation by educators of what constitutes digital scholarship is cause for the concerning impact of these practices in Australian schooling. While many dominant authors in the field acknowledge the likely transition towards a more digital, networked and participatory scholarly future, they warn that digital scholarship must be more than making traditional content freely accessible online (Goodfellow, 2013, p. 76). Rather, it involves providing access to content that allows scholars to create, produce, analyse, publish and disseminate new scholarship using digital means (Lewis, Spiro, Wang, & Cawthorne, 2015, p. 1). Thus, what this calls for is further examination in to the new skill sets needed by scholars to explore these possibilities. Can we expect our learners to be digital scholars without the skills necessary to harness their learning in this area? Furthermore, have we considered the implications of digital scholarship on our traditional achievement measures as the way our students are constructing knowledge is vastly different to what it once was (Loveless as cited in Starkey, 2011, p. 20)?

While the concept of digital scholarship is definitely not new in our schooling system, it appears that we are yet to harness this effectively to make a consistent change to the teaching and learning offered across our schools. Publications such as the New Media Consortium’s Horizon Report 2017 K-12 Edition make evident the importance of digital scholarship in the future of education. However, some of the significant challenges identified that are impeding developments in this area are, providing authentic learning experiences in a digital realm, enhancing ICT literacy and rethinking the role of teachers (2017). In alignment with authors such as Weller (2013), Scanlon (2014) and Starkey (2011), the Horizon Report suggests that digital scholarship is more than understanding how to use technology; it involves fluency and deep understanding (2017, p. 4). This involves teachers themselves becoming comfortable in the transformation of their role form the ‘sage on the stage’ to that of the ‘guide on the side’. Digital scholarship involves mentoring and coaching learners through complex digital world as they explore and delve deeper into new environments (2017, p. 4). Not surprisingly, this creates the need for teachers to be fluent in digital scholarship and the skills necessary to partake in this and engage with students in the four functions of scholarship.

Conclusion

While it is evident that scholarship of the digital age has morphed into a networked, online and participatory process, further research is needed in relation to the translation of digital scholarship into our educational systems. Australian schools in particular, seem to be lagging in their uptake of digital scholarship, with national standardised testing signifying that student achievement is not yet indicative of an increase in the ICT literacy needed as successful scholars. In fact, an area of concern is the willingness (or lack thereof) of Australian educators to embrace digital scholarship and the skills necessary to harness this in their learning experiences. Connecting students to a device or piece of software is not enough to ensure the transition between traditional scholarship and scholarship of the digital age. We must act to ensure our educators and learners can nurture, participate and embrace the affordances that digital scholarship provides. In echoing Dewey’s sentiment, we can’t prepare our students effectively for the future of continuous technological development in an ever-transforming world if we don’t reconsider our learning practices.

Reference List

Australian Council of Learning Academics (ACOLA) (2016). Skills and capabilities for Australian enterprise innovation. http://acola.org.au/wp/PDF/SAF10/Full%20report.pdf

Barr, A., Gillard, J., Firth, V., Scrymgour, M., Welford, R., Lomax-Smith, J., … & Constable, E. (2008). Melbourne Declaration on Educational Goals for Young Australians. Ministerial Council on Education, Employment, Training and Youth Affairs. Carlton, South Victoria.

Business Council of Australia (2016). Being work ready: A guide to what employers want. Retrieved from http://www.bca.com.au/publications/being-work-ready-a-guide-to-what-employers-want

CSIRO (2016). Tomorrow’s digitally enabled workforce. Retrieved from https://www.data61.csiro.au/en/Our-Work/Future-Cities/Planning-sustainable-infrastructure/Tomorrows-Digitally-Enabled-Workforce

Dewey, J. (1944). Democracy and education. New York: Macmillan Company

Esposito, A. (2013). Neither digital or open. Just researchers: Views on digital/open scholarship practices in an Italian university. First Monday, 18(1).

Goodfellow, R. (2013). The literacies of digital scholarship–truth and use values. Literacy in the Digital University: Critical Perspectives on Learning, Scholarship and Technology, 67-78.

Image – http://www.freepik.com/free-photos-vectors/infographic

Katz, R. (2010). Scholars, scholarship, and the scholarly enterprise in the digital age. Educause Review, 45(2), 44-56.

Levnajic, Z. (Ed.). (2014). Frontiers in ICT: towards web 3.0. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Lewis, V., Spiro, L., Wang, X., & Cawthorne, J. E. (2015). Building Expertise to Support Digital Scholarship: A Global Perspective. Council on Library and Information Resources. Washington, DC.

Lippincott, J., Hemmasi, H. & Lewis, V. (2014). Trends in digital scholarship Centers. Retrieved from http://er.educause.edu/articles/2014/6/trends-in-digital-scholarship-centers

Martin, L. (2016).The university library and digital scholarship: a review of the literature. In A. Mackenzie & L. Martin, L. (Eds.), Developing Digital Scholarship: Emerging practices in academic libraries (pp. 3 – 23). Facet Publishing.

McCain, T., Jukes, I., & Crockett, L. (2010). Living on the future edge: Windows on tomorrow. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

New Media Consortium. (2017). NMC Horizon Report: 2017 K-12 Edition. Retrieved from https://cdn.nmc.org/wp-content/uploads/2017-nmc-cosn-horizon-report-K12-advance.pdf

NSW Audit Office (2017). ICT in schools for teaching and learning. Retrieved from

https://www.audit.nsw.gov.au/publications/latest-reports/ict-in-schools-for-teaching-and-learning

Regional Australia Institute & NBN (2016). The future of work: Setting kids up for success. Retrieved from http://www.regionalaustralia.org.au/home/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/The-Future-of-Work_report.pdf

Scanlon, E. (2014). Scholarship in the digital age: Open educational resources, publication and public engagement. British Journal of Educational Technology, 45(1), 12–23.doi:10.1111/bjet.12010

Spector, J. (2010). Part 1 cognitive approaches to learning and instruction. In J. Spector, D. Ifenthaler, & P. Kinshuk (Eds.). (2010). Learning and instruction in the digital age (pp. 3 – 65). Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

Starkey, L. (2011). Evaluating learning in the 21st century: a digital age learning matrix, Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 20(1), 19-39.

Starkey, L. (2012). Teaching and learning in the digital age. Retrieved from https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.ezproxy.csu.edu.au

University of Queensland Library (2016).Student strategy 2016-2020 white paper. https://student-strategy.uq.edu.au/files/453/Student-Strategy_White-Paper.pdf

Veletsianos, G. & Kimmons, R. (2012). Networked participatory scholarship: emergent techno-cultural pressures toward open and digital scholarship in online networks. Computers & Education, 58(2), 766-774.

Vodanovich, S., Sundaram, D., & Myers, M. (2010). Digital Natives and Ubiquitous Information Systems. Information Systems Research, 21(4), 711-723. doi:10.1287/isre.1100.0324

Weller, M. (2011). The digital scholar: How technology is transforming scholarly practice. A&C Black.

![Librarian Signaling Quiet. [Photography]. Retrieved from Encyclopædia Britannica ImageQuest. http://quest.eb.com/images/154_2888635](https://theprivateteacher.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/image.jpg?w=585&h=409)